To prepare a cash flow statement, you'll use many of the same figures you use for a profit and loss forecast.

Every business should have an up-to-date cash flow statement ready to review. This financial document provides a snapshot of your company's financial state, particularly its ability to pay upcoming bills. A cash flow statement tracks actual cash flow. You'll use it to determine whether the money your business is bringing in (your business income) will cover the money you're sending out (your business expenses).

Some business owners prepare their own cash flow statement. Others hire a bookkeeper or accountant to prepare one. Either way, owners should have a basic understanding of how this document is prepared and why its numbers are important.

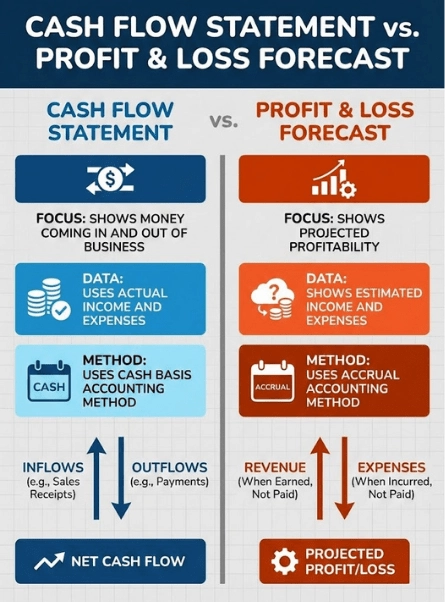

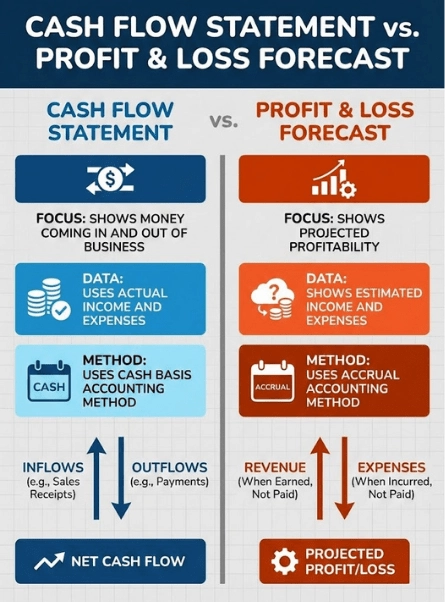

Cash Flow Statement vs. Profit and Loss Forecast

The primary differences between cash flow statements and profit and loss (P&L) forecasts are their purpose and methods of accounting. A cash flow statement shows a company's incoming and outgoing cash and uses a cash basis accounting method. A P&L forecast communicates a company's profitability and uses an accrual accounting method.

Purpose of Cash Flow Statement and P&L Forecast

The purpose of a cash flow statement is to show the money coming in and out of a business during a specific time period. It illustrates the business's actual cash on hand that's available to use—in other words, it's liquid cash. A business owner would refer to their cash flow statement to see whether they have enough money to cover that month's bills.

In contrast, a P&L forecast shows a business's profitability. A business owner would use a P&L forecast for financial planning purposes. You can use your forecast to create your budget and to plan for investments.

Accrual Accounting vs. Cash Basis Accounting

A cash flow statement uses cash basis accounting. Your statement should show your actual income—the money your business is paid, not how much it's owed—and your actual expenses. Then, at the end of each month, you should have a number that reflects how much money your business has left over after subtracting expenditures from the funds your business received.

If the end-of-month number is positive, you have enough money to cover that month's expenses. If it's negative, then you don't have enough money, and you'll need to come up with the difference.

Whereas a P&L forecast uses accrual accounting. Your revenue numbers reflect the amount your business made, including both money received and money still owed. For example, your revenue number for January might be $8,000 because you billed your customers $8,000 that month. But you might've only been paid $5,000 of the $8,000 owed. Your cash flow statement would say $5,000. However, your P&L forecast would say $8,000.

Meanwhile, your costs in a P&L forecast are estimated costs, not necessarily actual costs. The costs depicted in your forecast are anticipated expenses based primarily on your previous year's numbers, along with some other factors.

How to Prepare a Cash Flow Statement

To prepare a cash flow statement, you'll use many of the same figures you use for a P&L forecast. The main difference is that you'll include all cash inflows and outflows, not just sales revenue and business expenses.

For example, you'll include:

- loans

- loan payments

- transfers of personal money into and out of the business

- taxes, and

- other money that isn't earned or spent as part of your core business operation.

Also, in your cash flow statement, you'll record costs in the month that you expect to incur them, rather than spreading annual amounts equally over 12 months. This distinction is important because your business could show a monthly profit on a spreadsheet, but go belly up from lack of cash if you can't pay your bills on time.

For example, suppose you have a $4,000 workers' compensation premium and a $3,000 liability insurance premium due each July 1. You'll need to find a way to come up with real dollars then, not later.

Plus, if you make sales to some customers on credit (imagine a painter who invoices customers after the job is done rather than requiring full payment up front), your cash flow analysis should account for the fact that you won't get paid right away, as well as the fact that you might not collect some of the credit sales at all.

Here are the steps you need to follow to create a cash flow statement like the sample below. Do one month at a time.

Step 1. Enter Your Beginning Balance

For the first month, start your projection with the actual amount of cash your business will have in your bank account.

Step 2. Estimate Cash Coming In

Fill in all amounts you expect to take in during the month. You should include:

- sales revenue that'll actually be in hand

- collections of previous sales made on credit

- transfers of personal money into the business, and

- any loans coming into the business.

Basically, you'll need to include every dollar that'll flow into your business checking account.

Step 3. Estimate Cash Going Out

Enter all your projected payments for the month. You should include:

- Variable costs (cost of goods): These costs will fluctuate depending on your sales and production. They include inventory, supplies, materials, packaging, and sometimes labor.

- Fixed costs: These costs shouldn't change based on your sales and production. They include commercial rent, tax payments, and any loan payments.

Add these expenses to get your monthly total.

Step 4. Subtract Outlays From Income

Finally, subtract your total monthly cash-outs from your total monthly income. The result will be your cash left at the end of the month. That figure is also your beginning cash balance at the start of the next month. Copy this amount to the top of the next month's column and go through the whole process again.

Cash Flow Statement Example

On January 2 (as a New Year's resolution), Emme starts work on a cash flow projection for the next 12 months. She takes the following steps:

- She starts by putting the $5,000 she has in her business bank account in the "Cash at Start of Month" column for January.

- In her "Cash Coming In" section, she includes her cash sales (which are about 75% of her sales) and her credit sales (about 25% of her sales) on separate lines.

- She adds in all of the cash sales, but only 80% of her credit sales, because some percentage of her credit customers always take longer than 30 days to pay.

- In the "Cash Going Out" section, Emme includes her variable and fixed costs, putting the annual insurance premium she's about to pay in the January column rather than spreading it over 12 months.

|

Emme's Cash Flow Analysis |

|||||||||||||

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | ||

| Cash at Start of Month | 5,000 | 3,340 | 3,080 | 2,220 | 1,960 | 1,700 | –740 | –2,900 | –6,410 | –4,770 | –5,030 | –5,290 | |

| Cash Coming In | |||||||||||||

| Sales Paid (75%) | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 6,000 | 6,000 | 5,250 | 9,000 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 11,250 | |

| Collections of Credit Sales | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 1,600 | 1,600 | 1,400 | 2,400 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 3,000 | |

| Loans & transfers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total Cash In | 9,500 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 7,600 | 7,600 | 6,650 | 11,400 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 14,250 | |

| Cash Going Out | |||||||||||||

| Inventory | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | |

| Rent | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | |

| Wages | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | |

| Utilities | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Phone | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Insurance | 1,200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ads | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 280 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Accounting | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 0 | 600 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200 | |

| Loan payments | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Taxes | |||||||||||||

| Total Cash Out | 11,160 | 9,760 | 10,360 | 9,760 | 9,760 | 10,040 | 9,760 | 10,160 | 9,760 | 9,760 | 9,760 | 9,960 | |

| Cash at End of Month | 3,340 | 3,080 | 2,220 | 1,960 | 1,700 | -740 | -2,900 | -6,410 | -4,770 | -5,030 | -5,290 | -1,000 | |

It's easy to see why a cash flow analysis can give you a more realistic picture of whether your business will have the money to pay its expenses—in other words, sufficient cash flow to stay afloat—than a P&L forecast. A cash flow statement is especially important for companies that make sales on credit, because typically some credit sales aren't paid within the expected 30 days (and others not at all). A P&L forecast doesn't account for late or missing payments.

Cash Flow Analysis

After filling in her cash flow projection, Emme realizes that her account will go significantly negative in the slow summer months. She might not even be back in the black in December, her biggest sales month, because she's estimated that about $500 per month in payments on credit sales will be late. (Though if she eventually gets caught up collecting her accounts receivable, she'll be profitable for the year.)

But given that some customers will always pay late, she knows that if she can't reduce her costs in some way, she'll need some cash to tide herself over in some months, especially during the summer. Because she's already cut her own pay in half and trimmed other expenses to the bone, she'll have to either:

- bring in money from extra sales

- provide extra services, or

- get a loan from family, friends, or a bank line of credit.

Your P&L forecast, like Emme's, might say that your company will be profitable (or break even) over the next 6 to 12 months. But if your cash flow is projected to go negative, you're not going to be able to pay your bills when they become due. So you'll have to bring in more income or borrow some cash to cover the shortfalls.

Cash Flow Statement Template With Added Loan

Going back to her spreadsheet, Emme sees that a loan of $8,000 would cover the shortfall, even accounting for making a small loan payment. After December sales are in, she'd still have a balance of $5,000.

But Emme also sees that even if she gets a loan, it'd let her business survive only about 12 to 18 months of lower sales before again going cash-negative the next summer. In short, she needs to make sure that she can boost her sales back to her previous levels within the next 12 to 18 months or risk going in the red again before paying back the loan.

|

Emme's Cash Flow Analysis With $8,000 Loan |

|||||||||||||

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | ||

| Cash at Start of Month | 5,000 | 11,180 | 10,760 | 9,740 | 9,320 | 8,900 | 6,300 | 3,980 | 310 | 1,790 | 1,370 | 950 | |

| Cash Coming In | |||||||||||||

| Sales Paid (75%) | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 6,000 | 6,000 | 5,250 | 9,000 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 11,250 | |

| Collections of Credit Sales | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 1,600 | 1,600 | 1,400 | 2,400 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 3,000 | |

| Loans & Transfers | 8,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total Cash In | 17,500 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 7,600 | 7,600 | 6,650 | 11,400 | 9,500 | 9,500 | 14,250 | |

| Cash Going Out | |||||||||||||

| Inventory | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,500 | |

| Rent | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | |

| Wages | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | |

| Utilities | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Phone | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Insurance | 1,200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Advertising | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 280 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Accounting | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 130 | |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 0 | 600 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200 | |

| Loan payments | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | |

| Taxes | |||||||||||||

| Total Cash Out | 11,320 | 9,920 | 10,520 | 9,920 | 9,920 | 10,200 | 9,920 | 10,320 | 9,920 | 9,920 | 9,920 | 19,120 | |

| Cash at End of Month | 11,180 | 10,760 | 9,740 | 9,320 | 8,900 | 6,300 | 3,980 | 310 | 1,790 | 1,370 | 950 | 5,080 | |

Emme sets to thinking about how to come up with the extra $8,000. Her first thought is to have a one-time sale. But even at her usual 55% profit margin, she'd need to sell an extra $14,500 in clothes to generate that much gross profit. And discounting prices for a big sale would lower her profit margin, meaning she'd have to sell more. (If she sold her inventory at a 20% discount, her profit margin would be less than 45%, and she'd need to bring in more than $18,000 in additional sales.)

Realizing she doesn't have a realistic chance of selling that much inventory, she goes looking for a loan. When family, friends, and the bank turn her down, her last resort is to take out an $8,000 home equity line of credit (HELOC). The HELOC will allow her to dip into the loaned funds as needed to tide her over. In the meantime, she gets to work on a clever marketing plan to boost sales until better times are here.

Fixing a Cash Flow Problem

Now it's time for the next step, which is to focus on your current cash position with the goal of improving it. If cash is flowing out of your business significantly faster than it's coming in, you need to examine and strengthen three aspects of your cash flow:

- How and when cash comes into your business. You can increase sales and collect past-due accounts receivable.

- How and when it goes out again. You can reduce the costs of goods and labor.

- Where cash gets tied up in the meantime. You can reduce inventory and leased equipment.

Many of these steps will raise your profit margin.